So more about this project!

MI is in fact a Canadian organization based in Ottawa. They are running a variety of food fortification activities around the world, supporting vitamin and mineral supplementation programs where malnutrition is taking its toll on the most vulnerable populations. MI has been working closely with governments of developing countries to encourage the adoption of laws enforcing fortification in widely consumed products (think of iodized salt in Canada). In addition, MI has joined forces with a UNICEF immunization program against polio in Africa to provide strong doses of vitamin A to the children during administration of their shots. A home food supplementation program was implemented in India, through which mothers of households themselves are responsible for addition of a micronutriment concentrate to the family meals. In Malawi, yet another method of food fortification was successfully set up in small scale mills during cereal processing. MI is currently looking at the technical and social feasibility of the last two methods through the pilot project that Diallo and I are leading. The results of our study will influence the direction of the project when it is expanded to a national scale.

Engineers Without Borders hence got involved in a nutrition project by association. Since three of us short-term volunteers were sent to MFP Mali for the summer, and that there was a need for support in this partner project, it only seemed logical to send of one the three. The pilot project was divided into two phases, held in different regions of Mali. Purely to satisfy your curiosity, a region in Mali is basically the equivalent of a province in Canada, and there are 6 of them. The first phase of the project was held in the dry, sandy Mopti region and was originally scheduled to last two months. The second phase is also scheduled to last two months, but will be held in green, lush Sikasso. OK, I may have been a little generous with the word "lush", but the sight of a green field after living in the Sahel is truly breathtaking. So I joined the project on the fourth month, just in time to catch the end of the first phase in good old Sévaré. Cherchez l'erreur. Bingo! We were already two months behind.

Now, in practise, what this means is that I got the chance to tag along for a few visits with Diallo in some villages surrounding Sévaré. Diallo had a tight schedule to follow, and had a lot of pressure to complete the first phase in Sévaré, so we never really took the time to go through the “What?”, “Why?” and “How?” of the project together. It may seem a little ironic that we couldn’t take a day to cover the basics considering that the timetable had already been stretched by two months at that point. Indeed, that nearly drove me insane. I am extremely curious and analytical by nature, therefore when I am put in a situation where my questions find no answers, I become extremely restless.

As soon as Diallo came into the office in the morning, we would hop on his motorbike to head for the villages and we would only finish work very late, sometimes past dusk. Needless to say, a motorbike is not the best environment to discuss my questions - or anything for that matter. And our time in the villages was reserved for formalities with the villagers and going through one mean questionnaire. It was particularly difficult for me to do these follow-ups with clients at the MFP, and also those households who had tried the individually wrapped version of the vitamins, without having been present for the introduction, education and distribution activities.

MI is in fact a Canadian organization based in Ottawa. They are running a variety of food fortification activities around the world, supporting vitamin and mineral supplementation programs where malnutrition is taking its toll on the most vulnerable populations. MI has been working closely with governments of developing countries to encourage the adoption of laws enforcing fortification in widely consumed products (think of iodized salt in Canada). In addition, MI has joined forces with a UNICEF immunization program against polio in Africa to provide strong doses of vitamin A to the children during administration of their shots. A home food supplementation program was implemented in India, through which mothers of households themselves are responsible for addition of a micronutriment concentrate to the family meals. In Malawi, yet another method of food fortification was successfully set up in small scale mills during cereal processing. MI is currently looking at the technical and social feasibility of the last two methods through the pilot project that Diallo and I are leading. The results of our study will influence the direction of the project when it is expanded to a national scale.

Engineers Without Borders hence got involved in a nutrition project by association. Since three of us short-term volunteers were sent to MFP Mali for the summer, and that there was a need for support in this partner project, it only seemed logical to send of one the three. The pilot project was divided into two phases, held in different regions of Mali. Purely to satisfy your curiosity, a region in Mali is basically the equivalent of a province in Canada, and there are 6 of them. The first phase of the project was held in the dry, sandy Mopti region and was originally scheduled to last two months. The second phase is also scheduled to last two months, but will be held in green, lush Sikasso. OK, I may have been a little generous with the word "lush", but the sight of a green field after living in the Sahel is truly breathtaking. So I joined the project on the fourth month, just in time to catch the end of the first phase in good old Sévaré. Cherchez l'erreur. Bingo! We were already two months behind.

Now, in practise, what this means is that I got the chance to tag along for a few visits with Diallo in some villages surrounding Sévaré. Diallo had a tight schedule to follow, and had a lot of pressure to complete the first phase in Sévaré, so we never really took the time to go through the “What?”, “Why?” and “How?” of the project together. It may seem a little ironic that we couldn’t take a day to cover the basics considering that the timetable had already been stretched by two months at that point. Indeed, that nearly drove me insane. I am extremely curious and analytical by nature, therefore when I am put in a situation where my questions find no answers, I become extremely restless.

As soon as Diallo came into the office in the morning, we would hop on his motorbike to head for the villages and we would only finish work very late, sometimes past dusk. Needless to say, a motorbike is not the best environment to discuss my questions - or anything for that matter. And our time in the villages was reserved for formalities with the villagers and going through one mean questionnaire. It was particularly difficult for me to do these follow-ups with clients at the MFP, and also those households who had tried the individually wrapped version of the vitamins, without having been present for the introduction, education and distribution activities.

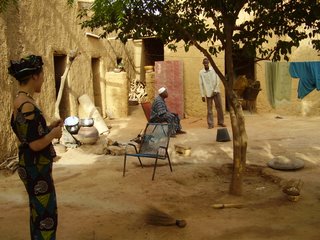

I truly enjoyed the village visits, mostly because my eyes could not absorb enough of the typical African scenes: the colorful clothes and buckets, the half-naked children, the old men sitting and chatting on cow skins, the straw roofs, the charcoal fire boiling some sweet green tea, a man in the shade performing traditional medicine on a suffering woman, the little chicks running between my feet, and I could go on and on… The interviews with the beneficiaries all occurred in Bambara, but the questions on my paper were all in French. The good part is that I knew what we were asking, but alas I could only pick up a word or two in the answer. I very much disliked the questionnaire, I knew that much. What a lame and limiting way to get people’s input! And how impersonal is it carry on a conversation over a piece of blinding white paper that clearly clashes with the environment I described earlier? I was still in observation and learning mode, and of course at this stage it was better to keep all these reflections to myself. I remember picking up wise advice from a past Junior Fellow who warned me from speaking up too fast…

Not even a week after I joined Diallo on this project, after visiting five villages or so, we had completed phase I. Diallo then left for Bamako on a 2-day trip to pick up the vitamins for the subsequent phase of the project to be held in Sikasso. He left me with some data entering, in other words countless questionnaires for me to capture in an Excel sheet. At this point I was thinking that it was too bad for me to have acted strictly as his secretary – a very sharp, inquisitive and nosy one, mind you – up until this point. I have some serious trust building to do indeed, and I realize that doing the bitch work (excuse my language) would do just that, but I do need to show certain competencies if I ever want to have a chance to contribute where I really want to make a difference.

My thought process in this case was that I was better off doing some mindless computing and taking the time to reflect carefully on my questions and problems with this whole project (and questionnaire!). I made a deal with Diallo that the time I was saving him should go towards a thorough Q & A session with me upon his return. And then he ended up being gone for 10 days… Ha! He returned to a five page document on my reflections and questions regarding the objectives and workings of the project. That’s what you get for leaving me unattended for too long! We were already in Sikasso by the time we ran through this document together. He realized that he was unsure of many of the answers, so we forwarded this monster to his boss with a nice introduction on who I am and another section on what EWB interns are out to accomplish, in case he was unclear on that. It’s surprising how misleading the term Engineers Without Borders can be sometimes, but I won't get into that. Anyways, a few days later, I found a reply in my inbox with a message from Diallo’s boss, informing us that he had worked on the answers with his own boss in Johannesburg, South Africa. Some answers were ok. But he insured us that they were impressed and encouraged by the serious thought and involvement that had been expressed. It felt like I got a test mark back and that there was a little star sticker at the top corner. But it all sure was nice substitute after bathing in confusion for over two weeks!